:

The term “Hindu” was not indigenous to the Indian subcontinent but was coined by Persian and Arab invaders to refer to the people living east of the Sindhu (Indus) River. The geographical term “Hindustan” initially described the land and people in the northwestern part of the subcontinent, now largely in present-day Pakistan. It carried no religious connotation and merely denoted inhabitants of a region—much like the terms “African” or “European.”

The philosophical term “Sanatan”—often co-opted today as Sanatan Dharma—predates the usage of the word “Hindu” and is found even in ancient Buddhist texts. However, “Sanatan” refers to an eternal, universal way of life or truth, not a codified religion with a single founder, scripture, or doctrine.

Notably, the Supreme Court of India, during BJP’s regime, was presented with the argument that “Hinduism” does not have a singular set of beliefs, practices, or tenets that can define who is a Hindu. This official stance itself undermines any claim of “Hinduism” being a religion in the conventional sense.

If there are no universally accepted doctrines, no unifying theology, no single holy book, and no clear criteria to determine who qualifies as a follower, then it is philosophically and legally inconsistent to classify “Hinduism” as a formal religion.

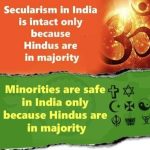

Rather, “Hinduism” is a fluid socio-cultural identity, artificially solidified under colonial classification and later politically weaponized. Its diversity has been replaced by a homogenized Hindutva narrative, which seeks to impose a rigid identity on a historically pluralistic tradition.

Thus, the term “Hinduism” as a religion is both historically inaccurate and intellectually dishonest.

1. Etymology and Historical Usage of “Hindu”

- The term “Hindu” is not indigenous; it originates as a geographical exonym used by Persian and later Arabic speakers to refer to people residing east of the Sindhu (Indus) River. Early Achaemenid inscriptions (6th century BCE) mention Hindush, a province in the Indus region (modern-day Pakistan)

“Hindu: A History” – Comparative Studies in Society and History (Cambridge University Press)

This scholarly article explores the historical evolution of the term “Hindu”, revealing its geographical origins and how it was later transformed into a religious identity.

- Linguistically, the transformation from Sindhu to Hindu is explained by a regular Proto‑Iranian sound change (s > h) occurring between 850–600 BCE. This shift is attested in Avesta (‘hapta-hindu’), Middle Persian, and Ashokan inscriptions (3rd century BCE) using variants like Hida loka for ‘Indian nation’

- For centuries, “Hindu” remained a regional or cultural label, not a religious identity. Even as Muslim chroniclers and Persian historiographers used the term during the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal era to contrast non-Muslims—but it continued as an ethnic/generic marker, not a codified religion

This article explores how the word “Hindu” originated as a geographic and cultural term, not a religious identity. It provides historical insights into how the term evolve /div>

2. “Sanatan Dharma” in Ancient Texts

- The phrase Sanatan Dharma (“eternal duty”) appears in classical literature. For instance, the Mahābhārata uses “esa dharma sanatanah”, and the Bhāgavata Purāṇa cites “yato dharmaḥ sanātanaḥ” (8.14.4)

This article explores the historical, philosophical, and cultural interconnections and divergences between Buddhism and Hinduism, including shared terminology, concepts, and periods of mutual influence and conflict.

- These terms convey a general, timeless moral order—not a unified religious system. They reflect a Vedic‑era concept of dharma, not an organized tradition labeled “Hinduism”, a concept that emerged only much later.

3. Supreme Court on Hinduism as a Religion

- In Adi Saiva Sivachariyargal Nala Sangam v. Tamil Nadu (2015), the Supreme Court declared that: “Hinduism, as a religion, incorporates all forms of belief without mandating the selection or elimination of any one single belief. It has no single founder; no single scripture and no single set of teachings…” ThePrint

- Under Article 26 and the doctrine of religious denomination, the Court emphasized there must be a defined system of beliefs and organization. Hinduism, being inherently pluralistic and non‑doctrinal, fails to meet that threshold ThePrint.

- In the Shirur Mutt case (1954), the Court established the doctrine of “essential religious practices”—routines or rites deemed core to a religion to be constitutionally protected. As there is no consensus across Hindu sects about what practices are essential, Hinduism cannot be rigidly defined or uniformly protected as a religion.

How the judiciary assumed greater theological authority than high priests of religions – A Moneycontrol Opinion piece by Shishir Tripathi (May 27, 2025), examining how India’s Supreme Court developed the doctrine of “essential religious practices” and positioned itself in matters of theology traditionally reserved for religious authorities :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}.

4. Implications & Analytical Summary

▶️ Origins

- “Hindu” began as a geographical/ethnic identifier, not theological. Derived from Sindhu, it became Hindustan (“land of the Hindus”) through Persian suffixation -stān

In this landmark case, the Supreme Court observed that Hinduism does not constitute a homogenous religion with a unified doctrine, founder, or essential set of practices, reaffirming its pluralistic and non-doctrinal nature.

▶️ “Sanatan Dharma”

- Ancient texts reference sanatan dharma conceptually, not institutionally. There’s no early textual evidence equating it with a rigid religious identity.

▶️ Palpable Legal Position

- According to constitutional jurisprudence, Hinduism lacks the doctrinal coherence, centralized scripture, founder, or uniform practices necessary for being registered as a traditional religion or denomination.

▶️ Conceptual Conclusion

- If a religion is defined by a unified structure or belief system, Hinduism defies that mold. Its diversity and lack of standardized creed were affirmed by the judiciary and rooted in its historical evolution.